Sofia Coppola enters the Salon Marie-Louise at the Ritz Paris looking exactly like someone you would encounter in a Sofia Coppola film. The scene exudes the same insouciant glamour: a shiver of tables are occupied by various grandees of the fashion and film industry, all discussing business, while a retinue of waiters in dinky uniforms manoeuvre baskets piled with breakfast breads.

Now 52, but indistinguishable from the girlish figure that starred in the Marc Jacobs fragrance ads shot by Juergen Teller in the early 2000s, Coppola wears quilted leather sandals, pale, wide jeans and a fluorescent-pink Chanel T-shirt: Barbiecore, if Barbiecore were chic. The jolie laide looks for which she was eviscerated when she starred in her father Francis Ford Coppola’s ill-fated The Godfather Part III have matured into a noble beauty, and yet she still has a youthful mien. She offers a handshake and a softly spoken greeting, then asks the waiter, very politely, if she could have a pot of tea.

Coppola is in Paris for the Chanel couture show, taking place by the river, for which she has helped with the set design. But she has enjoyed a long relationship with the city where she keeps a home in Saint-Germain-des-Prés. She lived there full-time with her husband, Thomas Pablo Croquet (aka Thomas Mars), lead singer of the indie pop band Phoenix, and their two daughters, Romy and Cosima, until they moved back to New York more permanently for their daughters’ schooling. The girls are currently summering with their French cousins, even though they are now “total New York kids”.

Coppola has worked as a Chanel brand ambassador with the artistic director Virginie Viard since 2019. Her latest project is a knitwear capsule for the house’s Scottish Métiers d’Art brand, Barrie – “my dream travel wardrobe”. She is also, half-seriously, trying to persuade “the guy who does the sports stuff” to make branded paddles for pickleball.

It’s an easy collaborative relationship that was cemented when she first interned for Chanel, under Karl Lagerfeld, when she was still only 15. “[The actress and Chanel muse] Carole Bouquet was friends with my parents and she arranged for me to be an intern in the summer,” she explains. She speaks in slow, softly looping sentences with Valley Girl inflections that recall someone far younger than she is. “And then I went back the summer I was 16. Gilles Dufour [Lagerfeld’s then assistant] took me under his wing. It was a big moment in my life.” “I mean, it was the ’80s,” she continues, “and the height of fashion was Paris, and Chanel. And then there were all the models, like Veronica Webb, and a lot of these cool, older kids… and it was just so exciting to do. I mean, I grew up in the country in California, and there was no connection to any of that.”

Coppola did grow up in the country, but no one would say she had an ordinary childhood. Her parents, Francis Ford Coppola and the artist and documentary filmmaker Eleanor Jessie Coppola, sat at the centre of a sprawling cinematic dynasty and holidays were spent on different sets around the world. Initially, she resisted doing anything so “lame” as to enter the family business, unlike her cousins Nicolas Cage or Jason Schwartzman, her aunt Talia Shire, brother Roman, grandparents, uncle and most others members of the clan. As a fine-arts student at CalArts she anticipated becoming a magazine editor, or going into fashion, or photography, before finding that filmmaking “combined all the things I like”. She wrote, produced and directed her debut feature, The Virgin Suicides, starring Kirsten Dunst and Kathleen Turner, in 1999. It immediately established the dreamy, tragicomic, feminine aesthetic that is a signature of all her films.

This autumn will see the release of Coppola’s eighth film, Priscilla, starring Cailee Spaeny and Jacob Elordi, a biopic adapted from Priscilla Presley’s 1985 bestseller Elvis and Me. It being a Sofia Coppola film, however, it is not a biopic as other people might conceive. The film depicts Priscilla Beaulieu’s first meeting with Elvis as a 14-year-old schoolgirl in Wiesbaden, West Germany, near where Elvis was posted on national service in 1959. It then follows her move to Graceland in the early ’60s, her marriage after a long (and unconsummated) four-year courtship, and ends with the couple’s separation in 1972. Coppola’s film tracks Priscilla’s transformation from mousey schoolgirl to shellacked and idealised virgin bride in a dreamscape of music montages and make-up. It is framed exclusively within the female experience, a world of excruciating boredom, sexual exhilaration, loneliness and lots of pills.

The film was shot on a shoestring budget, outside Toronto, in only 30 days. Coppola had previously been working on a big adaptation of Edith Wharton’s The Custom of the Country when the funding fell apart. It offered a chance to revisit a story she had been mulling over for years. “I had looked at Elvis and Me maybe 10 years ago… But, on reading it again, it spoke to me.” She was reminded of “my mom’s generation, and how my mom grew up with a big force of a husband”, but also the feelings that surround an early love. “All those stages of transition, from girlhood to adult womanhood. I felt it was relatable,” she says.

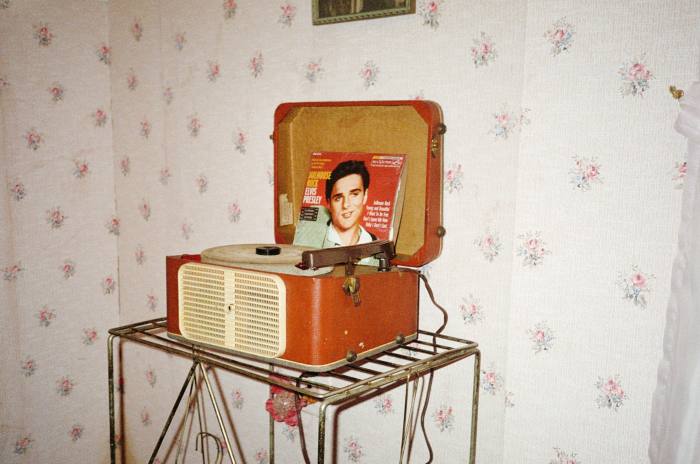

Much of the film’s aesthetic was inspired by William Eggleston’s 1984 series Graceland, the photographer’s portraits of Elvis’s unoccupied home. “I loved doing something really Americana, and Memphis,” says Coppola, “because that’s something foreign to me. I loved the hairspray, and the glamour, and the façade. And I thought a lot about Eggleston’s photos, and that colour, and the shag carpet, and Graceland as a motif for this American dream.”

Coppola has long shone a light on lives of exceptional privilege or celebrity only to expose the vapidity at their heart. Her films often feature a young woman inhabiting what seems to be a fantasy existence – a five-star hotel in Tokyo, the Palace of Versailles – only to reveal that they are isolated in a cold, unfamiliar world. “You think, ‘Oh, all these things are going to make for the ideal fantasy life,’” she says, “and then it’s this fairytale that turns out not to be so fun.” If the long scenes of Spaeny walking down empty hallways become a little tedious, it’s probably a fair reflection of how Priscilla felt.

Likewise, Jacob Elordi’s Elvis is a far cry from the coiffured charisma bomb as seen in Baz Luhrmann’s recent film. This Elvis exists on a diet of uppers, downers and Grandma’s Southern cooking; he may be impotent, he’s prone to drug-induced hot tempers and overwhelmed by dark creative moods. “I didn’t want to villainise him,” says Coppola, but she has been fairly honest about his flaws. “It was the most non-Elvis movie about Elvis. But I didn’t want [the film] to be about a drug addict. I like to leave things to the imagination. It’s just not my style to be in your face.”

Even so, there is something deeply uncomfortable about watching a 24-year-old global icon grooming a schoolgirl still barely in her teens. Did she view Priscilla through a #MeToo lens? “I just put myself totally in her perspective and tried to make a film about what if you were her. I didn’t think too much about all the different perspectives. Yes, it was a different time, different culture, but there are elements that remain the same…” I suppose if Harry Styles turned up and said, “I want to take your teenage daughter off on holiday”, you’d be pretty churlish to refuse? “Yes, your daughter would hate you forever,” laughs Coppola, before adding, “I think her perspective is quite relatable. I had crushes for a long time at that age.”

The film’s allusions to addiction and sexual violence may be gentle, but they’ve inflamed the Elvis estate: an unofficial statement issued shortly after an early screening described the film as “horrible” and they’ve refused to let Coppola use any of his music for the film. “The Elvis estate is not happy,” says Coppola, who seems unbothered, even amused, at the possibility of an Elvis film without a single song by the King. “I remember Priscilla’s manager saying, ‘The Elvis fans are not going to like certain things.’ And I was like, ‘I’m not making it for them.’”

Coppola is a fastidious curator. Whether it’s chaotic, suburban teenage bedrooms or nighttime Tokyo neons, her sets conjure a lush, romantic universe. Many of these are documented in a new book, Archive (published by Mack), which looks at the moodboards behind each Coppola film: here is the painting by John Kacere that inspired the shot of Scarlett Johansson in sheer knickers in Lost in Translation, a Guy Bourdin image that informed a frame in Marie Antoinette. Everything is flawless, soft and girly: there are dozens of delicious on-set shots.

But not everyone understands the details. Some find Coppola’s obsessions bordering on slight. The director remains unapologetic about her love of surface. “The trappings, all the more exterior things, are all part of it. To me it’s part of the story and the emotional feeling in it.”

“Sofia has a knack for combining elements in the frame… like Fellini,” says Rainer Judd of Coppola’s aesthetic. The actress and president of the Judd Foundation (she is Donald Judd’s daughter) has been friends with Coppola since she “looked out for her” during that Chanel internship in Paris when they were both 16. “She has a sensitivity about the world that works on your unconscious,” she continues. “She experiences the world in a more compact way.”

Coppola doesn’t dwell on the agenda. While she is keen to get “the facts right”, she doesn’t shoot her film through any frame. Priscilla could have been a feminist entreaty: instead the ethics and motivations are quite blurred. “Sofia’s not a heavy person,” Judd continues. “She’s not overly intellectual. While her subject matter is very intellectually rigorous – and people will think about her work – she’s not coming at it from a heavy point of view.”

“I just want to experience someone else’s world for that moment,” adds Coppola. “That’s all I’m trying to do. When I was starting out [as a director] my dad gave me this encyclopedia of poetry. And he was like, ‘Film is poetry.’ It doesn’t have to explain. Poetry is just a feeling. And I just want to feel.”

With their slowly unfurling narratives and uniquely female perspective, Coppola’s films could not be further from her father’s ultra-macho oeuvre. Nevertheless, growing up steeped in cinematic practice, she learned early to develop an uncompromising point of view. One wonders also whether Priscilla might have an autobiographic seam. “My life wasn’t anything like that,” replies Coppola. “But I can put myself in Priscilla’s shoes… Having grown up with a powerful, charismatic person… The world revolves around them in a way. And so, even though my life was nothing like that, I have a vantage point where I can relate.”

Sofia collaborates closely with her brother Roman, her daughter’s namesake, who has worked on all her films: “He’s almost like a therapist – he really understands me, and helps me figure out how I would do it, whereas a lot of other directors would be like, ‘Do it their way.’” She’s less receptive to her father’s suggestions, “because I don’t want too much input, and my dad has strong ideas.” The two of them are extremely close, but she doesn’t want him near her films. “He’s looking at it from his perspective,” she laughs, “and I don’t want a male perspective on my world.”

Coppola has a certain toughness that Judd says is very much the product of growing up around an alpha man. “There are a few of us daughters of big, big creators of the 1970s and inadvertently we have this incredible confidence. These men maybe weren’t doing everything right by their wives, but they gave their all to their daughters. And the result was these extra-endowed women: young women who were given balls.”

FT Weekend Festival

FT Weekend Festival returns on Saturday September 2 at Kenwood House Gardens, London. Book your tickets to enjoy a day of debates, tastings, Q&As and more . . . Speakers include Leïla Slimani, Neil Jordan, Deborah Findlay and many others, plus all your favourite FT writers and editors. Register now at ft.com/festival.

Coppola is peachy-gentle but single-minded: one can’t imagine she will direct a Marvel film. In 2014, she was slated to make a live-action remake of The Little Mermaid, for Working Title and Universal, but she walked off the project when artistic differences arose within the studio.

“It’s so hard to make a film these days,” she says of the current landscape (she is speaking shortly before the SAG-AFTRA strike, which prevents actors and directors from promoting movies, although exempts creatives, of whom Coppola is one, promoting independent films). “I have an established career and I still have to beg to get enough money to try to make a film. I can’t even imagine starting your career right now – it’s just much more commercial and safe, people don’t want to take risks.”

Coppola burst onto the scene as one of a new wave of directors in the late ’90s, along with Paul Thomas Anderson, Darren Aronofsky and Wes Anderson. But despite having been one of the first female directors to be nominated for an Academy Award and the second to win Best Director at the Cannes Film Festival, she still finds the patriarchal film system pretty closed.

“It’s still straight guys making the final decision, so they aren’t always interested in what I’m interested in,” she shrugs. “There aren’t a lot of women and gay men in charge at the very top, so it’s always a struggle to talk to guys that are not so into my [point of view].” Then again, she’s not complaining. “I never really cared… I just liked to slip by and do my thing without too many people paying attention. You have freedom in that.”

Although she frequently dismisses her career as a series of dalliances, Coppola is happiest when working on a set. Youree Henley, who has worked on her films since 2009, and Lorenzo Mieli, the producer who worked on Priscilla, both attest to her collaborative instincts, and her willingness to listen and adapt. “I would describe her as an auteur,” says Henley. “I guess part of her success is her taste and confidence. In an industry that is really reactive she doesn’t get caught up in what other people are doing, she really just does her thing. Also, she is fearless – she’s not afraid of taking a counterintuitive road. She can jump from one thing to another very quickly. She lives among us… but she has this wonderful ability to tune out all the noise.”

Coppola’s plans post-Priscilla are currently hazy. She typically takes a while between different projects, does some Chanel work, spends time with her daughters, and reads a book or two. Having shielded her daughters from the vicissitudes of celebrity, she is fairly sanguine about them picking up the family trade. “My older daughter is into music and acting and stuff,” says Coppola of Romy’s ambitions. She has always taken her children on set: “It’s exciting to see all the different things you can do.” Romy’s skills as a performer were tested in March when she published a TikTok about being a “nepo baby” that amassed some million views, went viral, and then completely disappeared. It was either the cringiest expression of privilege ever recorded or, more likely, considering her mother’s own sly brand of humour, a genius piece of satire.

Coppola is hoping that the Wharton project might yet be reignited. In the meantime, she’s looking at other things. Lately, she’s been reading The Copenhagen Trilogy by Tove Ditlevsen: “It’s bleak, but it’s so good.” She “really liked” Past Lives, the South Korean film by Celine Song that premiered to great reviews at Sundance earlier this year, and enjoyed HBO’s Succession: “It’s a little bit talksy for me, but I like the Loro Piana, and the settings. At night, I don’t want to watch something stressful. I want to have a little hope.”

When I mention that I find her films quite melancholy, she seems surprised. All the fleeting loveliness and beauty makes me nostalgic for the potential of lost youth. “I know,” she sighs, of her long obsession with “transition” and adolescence. “I think I’ve done enough teenage now. I need to move on.”

Then again, there’s something endlessly appealing about watching young people with a future. Plus, teenagers look great in clothes. As usual, she doesn’t overthink it. “I just hope there’s always something hopeful, and romantic,” she says. “And I want to have a future, yes.”